A picture of HKUST. Photo: Angelica Kosasih

I was inspired to write this blog post only last night, when I was about to sleep. Having spent almost three weeks in Cambodia with another close friend of mine, Vaishak, in order to observe the implementation of a mobile health (mHealth) project, we have – during the spare time – frequently talked about reminiscing our undergraduate lives back in our university, HKUST. We talked about our friends, moments, experiences, and everything else about life in general. And that was the point that I became so motivated to write something about my overall impression, feelings, and reflection about what I have learned in the last 4 years of my university life here.

Now approaching the end of my undergraduate life – and soon to resume another 2 years of research postgraduate studies in the same university in less than 3 months, I did a flashback to 2013, the first year I entered the university. At that time, I did not put HKUST into my utmost priority: originally, my actual priority was to opt for Singaporean universities. Indeed, of all 6 universities in both cities that I had applied during my high school, HKUST was the last university that I opted for: I submitted my application almost 1 day before the application deadline. However, HKUST was also the first university of all I had applied to give me an admission offer, although it was still conditional.

The major that I chose was also considered unusual: Global China Studies. I have always had an academic interest to strengthen my expertise in international relations and political science. When I was looking at this major, I was like, “What the heck is this? But it looks interesting.” Given my intense interest about international relations, especially about the “rise of China” discourse, I decided to give it a try. Global China Studies, indeed, was the only major program that I applied to.

Still, despite HKUST having given me the first offer, I was still waiting for application results from Singaporean universities. NTU had rejected me beforehand, and I was already not too confident about NUS results. SMU (Singapore Management University) was putting my application result on hold, as I had to retake its SAT test before its deadline in May that year; for the first SAT test I took, I scored 1890, 10 points below their minimum requirement (1900). I took it for the second time, and this time, I got a test score of 1950. How ‘briefly’ excited I was at that time, until a hidden voice inside my mind suddenly urged me to change my decision, and accept HKUST admission offer instead. I truly have not a single hint of how that ‘divine intervention’ occurred: the inner voice just kept pushing me to accept HKUST offer. There, I made what was considered by my parents a big “U-turn”: after having spent quite a lot of money for SAT preparatory courses in order to get into SMU, I fixed my decision to go for HKUST instead.

All this was happening despite City University of Hong Kong (CityU) also giving me an admission offer, with a full-coverage, 4-year scholarship guaranteed. My parents at that time had urged me to reconsider my HKUST offer, but somehow the inner voice within my mind – ‘divine intervention’ second time, perhaps? – kept urging me to “have faith”. After further deliberation with other family members, including my aunt and my cousin, who used to study in CityU, their suggestion was that I pursue my studies in HKUST. Near the end of August 2013, I set off, for the first time in my life, for a life overseas.

Before setting off to this university, I have never really left my hometown. I was born and raised in Medan (Indonesia’s fourth most populous city), and lived my life there for the first 18 years of my life. And so were my parents: they were born and raised in the same hometown as I did, and they have lived almost their entire lives there for close to half a century. We occasionally had annual overseas trips to neighboring countries, but none in my family had ever really moved to another place before. Our lifestyle has been pretty much the same lifestyle for most other people in my hometown. We lived a pretty secure, stable, middle-class life, with a limited sense of adventure, and a constant craving for stability. As I had recurrent asthma attacks when I was a young child and had to be occasionally hospitalized, my parents – to a certain extent – were quite protective of me. But I could understand their reasoning and concerns: they are simply afraid of me suffering from sudden asthmatic conditions. The only sport I did (and still do) is doing athletics: I joined an athletic club in my school for almost 3 years, and it kind of reduced my asthmatic tendencies. None of my family members has learned swimming, and neither have I, but at least we do running and badminton. My childhood was not too special either: I was frequently a top performer in my class, pretty active in extracurricular activities, and got to know a lot of friends and acquaintances, but in reality, my friendship circle was quite small and limited. I became a class monitor for 2 years, and I became what my fellow friends described me as a “good boy”, always leaning to teachers’ advice. When I moved to Hong Kong for the first time, these were all the traits that I had carried with me: “good boy”, study-hard personality, nerdy, not so into adventure, a bookish person, and one craving for stability.

However, adjusting to life here was barely as easy as I had experienced for the first 18 years of my life in my hometown. Perhaps I just want to be honest here, but for the first few days when I was here in HKUST, I actually always ended up weeping when I was lying in bed, going to sleep. The dorm room was small, perhaps only one-third of the size of my room back in my hometown, and the furniture was dusty. At first sight, I had yet to fully realize about the even more miserable realities being faced by a certain proportion of Hong Kong population living in so-called “subdivided flats”, whose houses (literally houses) were even smaller than the double-room I had stayed in. Indeed, the double room I stayed in was quite ‘spacious’. That was already my first struggle.

Secondly, I was only one of a very select few among international students who have enrolled in this Global China Studies program, at that time barely two years old. When other academic programs had been compared to as ‘adults’, this program was still like a toddler. That sense of rarity further isolated me, coupled with the fact that I am the only Indonesian student (until now, literally) who enrolled in this program. Most other people would opt for either business or engineering majors. Also, I did not have a strong connection with most local students undertaking the same program as I did, given what Willy Brandt described as “the wall in the mind”. There, I felt constantly lonely given that I sometimes did not really know to whom I should share my insight, my knowledge, and my ideas with.

Third, coping with life in HKUST was like overcoming a constant, massive, and unending cultural shock. Even if I have to be completely honest, after four years studying here, I occasionally still face a significant cultural shock. I love the diversity of this place, but it is the same diversity that always tests the degree of my open-mindedness. I got to know a lot of international friends from many other places across the world, such as Malaysia, South Korea, India, China, Sweden, Poland, France, Switzerland, United States, El Salvador, Singapore, the Philippines, Russia, and so many countries else, including local Hong Kong friends, and in particular, some new Indonesian friends here. And to make it even more twisting, their backgrounds are more colorful than their nationalities can tell: Korean friends I know who have spent years outside their home countries, in a range of places from the United States, to Southeast Asian countries, and even more interestingly, in the Middle East. A half-Chinese, half-French, but having lived in different parts of the world. A half-Lebanese, half-Italian, who is fluent in five languages. A half-Hong Kong, half-Korean, who spent much of her life in China, carrying a Cantonese-sounding name, but speaks no Cantonese and has Korean and English as her native languages. A 50% local, 25% white American, and 25% Japanese American, who lived almost all his life in Hong Kong. A half-Singaporean, half-Filipino. An Israeli who served in the army and had recounted to me his experiences combating Hamas militia. An Indonesian who studied in France and communicated to her parents in three different languages: Indonesian, English, and French. A Taiwanese, but knows as many Indians, Pakistanis, and South Asians as she befriends her fellow Taiwanese. An American hailing from a very conservative town in a conservative state who has lived in Morocco, Germany, and other parts of the world. A Polish libertarian who happens to love Indian vegetarian food. A South Indian living in Chennai, but does not speak fluent Tamil. Malaysians that spent most of their lives in Shanghai, and numerous other cities across the world. A South Korean who lives in Vietnam almost all her life, and has almost no linkages to South Korean contemporary culture. A Mainland Chinese woman that has more international than her fellow Mainland Chinese friends, and who imbibes herself into arts. A half-Indonesian, half-Japanese, who studies in a Canadian international school and speaks 7 languages. A half-Swiss, half-Finnish with partial family roots in South Africa and is currently in Stanford. Indonesians with 1% to 10% Dutch roots. Tunisians that toppled their own government in the Arab Spring. This excludes people of very different personalities. Ultra-tough nerds spending time mostly in their own rooms. An Indonesian friend coping with her mental illness while working hard on her startups. An Indonesian friend who loves metal music. A quirky Indonesian woman who loves arts and robotics and loves to randomly draw flowers on one’s research papers and randomly spams one’s Whatsapp account. Party animals, who love being drunk and partying until the bars are all closed. Work-hard-play-harder corporate world-aspiring girls. An anti-social person who fakes laughter amid all his personal struggle in his university life. One who loves blabbering about his experiences having sex with strangers. Conservative, very religious Christians who frequently asked me to join in their gathering sessions. Hipsters who love arts. Globally-minded travelers. Some friends who like to share manga jokes, many of which can be perverted. A French-Swedish woman who occasionally smokes and listens to French classical music, but is fun to talk to. A Mexican roommate who only wears black T-shirts, and who only has black T-shirts, and who spends over 50% of his time in laboratories. A young American from Montana, studying in Texas as the first place he’s out of his state, and making Asia the first place he’s outside the US, and who falls in love with Korean indie music. The first Indian student to enroll in Science program, when most people are either in business or engineering. An aspiring Indonesian wildlife activist who spent his gap semester in a jungle. A roommate who loves to talk about investments. An Indonesian senior who was very humorous, but also very introverted, and who is now pursuing a PhD. Another Indonesian senior who always scored almost perfect GPA score, but is also very religious and committed to his long-distance relationship. Dank meme-loving Indians. Cultural ignoramus, etc. Some are absolutely cultural shocks, but I also gradually embrace them as I let my mind increasingly open.

I gradually cope with these struggles, but coping itself has always been easier said than done. At certain points, sometimes one may wonder whether ‘being open’ itself was ‘too much’ to bear. But I understand that the values having been inculcated at me in the last 18 years are strong, and oftentimes it will take a gradual process of acceptance in moderating my own values vis-à-vis theirs.

In my first year of study, I participated in a university-supported student development program known as “Redbird Award Program”. This was my first exposure to extracurricular activities outside my hometown, and outside the context of near-similar activities by which I have participated during my high school. There I got to know some of the first people that I have described above. Some of the workshops were pretty monotonous, but the most challenging thing was the ‘wild camp’ training that they organized. It was a 3-day, 2-night camping activity in a country park in Hong Kong, and there, we had to scout through different peaks, walk through rocky trails, and occasionally climbed through some of the rocks in the peaks. Albeit I have asthma, I did not want this disease to affect my overall activities. Accepting that as a challenge, I participated in the camping activity.

The next challenging thing was to initiate a student-led project as part of the ‘graduation requirement’ from this program. I was initially running out of ideas, until I got a sudden flash of inspiration from Humans of New York. (thanks, Brandon Stanton!) There, I began to pitch the idea of “Humans of HKUST” to some friends, and thus this project began. Together with 2 Indonesian and 1 Malaysian friends, as well as several other volunteers, we started to interview people, made portraits of them, using our pot-luck equipment. None of us had high-resolution cameras, therefore we only relied on our own smartphones.

As time goes by, I gradually adjusted my life here in HKUST, and in Hong Kong in particular. I learned to navigate various MTR stations on my own, visited my aunt, my cousin, and my uncle once in a month on my own, and learned to act fast. Tapping Octopus cards, paying with cash, strolling fast, arranging my weekly schedule on my own, learning some basic Cantonese, getting to know which public buses to take, doing weekly laundries, cleaning my dorm room, moving items to another dormitory, all the while managing assignments, papers, and projects, sometimes group-, sometimes individual-based.

Simultaneously, following my seniors’ recommendations, I began to actively participate in research. I once aspired to be a novelist, having made 12 failed attempts to complete 12 different novels in various genres. I tried fantasy based on Lord of the Rings trilogy, science fiction based on Star Wars, as well as social critique works based on contemporary issues from various non-fiction books I have read. I was actually very happy when – on my 13th attempt – I eventually succeeded to complete a novel. But it was a violent work of fiction. I was inspired by a World Press Photo-winning work about portrait of a Danish prostitute, who is also a single mother who needs to take care of her three daughters. The 13th novel, pretty much, with different settings and refined plot, was inspired on this portrait. But I decided to put my work in shelf for an indefinite period, now starting to focus on academic research instead.

My first research project, beginning in July 2014, was about China-Africa economic relations with Professor Barry Sautman, by which I was tasked to create a database of Chinese companies across African countries, as well as their workforce localization rate. In the end, I managed to create data entries for more than 800 Chinese companies across the continent, an uneasy task. From this project onward, I undertook further research commitments in various other projects. The second one – beginning in 2015 – was about democratic development across the world, this time with Professor Sing Ming. But we rarely had face-to-face meetings, and we mostly exchanged our correspondence through email messages. Still, the project had to go on, as different professors have different ways of communication. First, I was assigned to do a case study about Thailand, but afterwards, I was asked to do a comparative analysis of Malaysia and Venezuela. The third one – commencing in 2016 – was a self-initiated independent study research project about One Belt, One Road initiative, with Prof. Barry Sautman as my advisor. The project, to be quite honest, was already as vague as the initiative itself: so much sloganeering, we truly don’t know what the initiative essentially is. Still, I managed to create a self-compiled dataset of over 900 Chinese-led infrastructure projects (in both China and in OBOR countries), although I have no idea – at all – how accurate they were in terms of their alignment with the initiative. Lastly, this year in 2017, I undertook another research project about anti-corruption campaign in China under Xi Jinping, this time with a newly recruited faculty member, Professor Franziska Keller. I created another dataset of over 300 officials having been removed under the campaign, as well as their replacements. Looking back to 2014, I actually never expected – at all – the pathway that would lead me to these projects, from one to another. My original dream of becoming novelist is now completely set aside, as I made peace with the existing reality, and now develop my new interests in academic research. Still, in spite of these 4 different research projects, I have yet to manage to publish a single work in an academic journal. And, guess what? I gradually took the bitter pills of rejection when my papers were either rejected by think tanks I submitted to, or when my professors pointed out flaws with the databases I have curated. They are bitter pills, but I fully understand the tough reality of academic world: no matter how meticulous your research is, there will always be loopholes with our work, and thus, grounds for rejection. I read no less than 90 academic papers for the China-Africa links project, 30 papers for case study about Thailand, close to 50 papers for comparative studies of Malaysia and Venezuela, over 20 papers about One Belt One Road initiative, and almost 20 papers about anti-corruption campaign in China. At least I am personally proud I have read those papers, although it took quite a toll at me.

Research projects, in one way, are a method for myself to strengthen my academic CVs, and to a certain extent, a way to cope with cultural-related shocks that are still lingering for myself, and to reduce a fluctuating sense of loneliness. Reading papers and books enriched my knowledge significantly, as well as improved my understanding of a research framework for an academic paper; moreover, research projects made me preoccupied for my already hectic schedule. Occasionally, however, I was bored with constantly reviewing academic papers, but if I stopped reading the papers, sometimes I would feel uneasy with myself, especially the recurrence of “wasting own time, doing nothing” mindset.

Studying in HKUST meant a high expectation, entailing everybody to ‘get busy in almost everything’, from non-trivial matters to so-called ‘world-changing’ research projects. Most faculty members have at least more than 1 research project to manage individually, and there is a constant pressure among the faculty of a ‘publish or perish’ culture. Because after all, research output is what accounts for HKUST’s high ranking among QS (Quacquarelli Symonds) and THE (Times Higher Education). Students would also be challenged to get busy in various activities, be it student clubs (locals refer to them as “societies”), seeking internships, creating startups, joining sports teams, or getting involved in on-campus jobs, joining Robotics, community service projects, part-time research assistants, doing global health projects, etc. For me personally, for 4 years in my life, I think I have spent 50-80 hours every week doing stuff related to the university, ranging from extracurricular activities (Redbird, and then one of my friends’ art-appreciation club), research projects, reading course materials, writing course papers, conducting literature reviews, and leading other independent projects (such as Humans of HKUST).

Writing this makes me look like a typical student ambassador. But I want to be honest here. It is a good thing to be involved in so many activities, and personally, having my life undergoing this pathway has provided me with numerous valuable benefits for my personal development. Nonetheless, simultaneously, such approach has its own costs. I often perceive that relationships become superficial as everyone is so committed in numerous projects and activities, so much so that the degree of interaction remains shallow and constrained to student-related discussions only. I may have known a tremendous number of new friends while in the university, but if I have to be very honest, our relationship is quite shallow, mostly limited to “hi-how are you-bye” conversations. That is why in my first year I was not involved in many activities, mostly limited to Redbird Award Program, writing my own novel, coordinating with others for Humans of HKUST project, and absurdly enough, signing up for iGEM – a synthetic biology competition (which has nothing to do with my major), and lastly, helping to organize a one-week cultural exchange program for international students in June 2014. Moreover, sometimes I continued to wonder about what true friendships are, given what I perceive as a superficial nature of a large part of my relationships, and the “impostor syndrome” that is quite obvious among a large number of my friends and acquaintances.

Still, I can not deny the fact that I have managed to befriend a large number of brilliant and insightful minds in this university. Individuals, whose ideas and values I would have never preconceived of had I stayed in my hometown for the rest of my life. Someone who’s very keen into startups, having failed twice, and still very resilient. A self-taught programmer who also indulges in deep, philosophical discussions. Someone who truly showed me what ‘art appreciation’ is. Someone who introduced to me dank memes (and how I end up liking a lot of dank meme pages these days). Someone from my major whom – for the first time in my UG life – I could deeply relate with, given her deep interests in international relations. Someone who shared with me his experiences of participating in a mass protest to topple an authoritarian government. Some persons who showed me their research progress from various fields. A professor who has lived in Mao-era China and witnessed – in his own eyes – Tiananmen protests in 1989. Getting to know Jewish professors for the first time (all the while shattering my prior stereotypes of them). These, I would say, are not superficial relationships; I truly get to know them not only on their surfaces, but also to understand their real values within their hearts.

And one way to maintain my constant communication with some of these new friends (except faculty members) would be to create a chat group in Whatsapp, which I simply titled “Hangout!”. I first started the chat group in February 2015, as I was about to celebrate the first Chinese New Year outside my hometown. At first sight, my original aim of creating this chat group was only to organize the first Chinese New Year dinner. I did not have expectation, in that earliest moment, that this group would continue to exist. It was only after that dinner that I decided to continue using the chat group to organize other hangout activities. Moreover, I was proud that the group has so many people from multiple backgrounds and interesting personalities. That was the first moment when I felt so internationally-minded; moreover, my objective of this chat group was relatively straightforward: I just want to be as inclusive as possible, at least for some of the persons within the group to never feel lonely. I have felt moments of loneliness for the first two years of my study, therefore I simply hope that the chat group can become a ‘safe haven’, especially some of my close friends who also shared the similar feelings of loneliness.

But perhaps my mistake was that I had been too inclusive that I arbitrarily added people into the group, so much so that it became a bubble of its own. As time goes by, the group size grew significantly. Indeed, it grew too large, from a group of 12 people (all of whom were in the very first hangout) to, at one point, over 84 individuals, most of whom hardly ever know each other. Many of them have since left the chat group. In a Chinese proverb, one would literally translate it as “people mountain, people sea” (renshan renhai 人山人海). For me, it was more like “people come, people go”. Many have left, but since then, many new friends of mine have also joined the group. I learned that moment that expanding the chat group too rapidly was a fatal mistake: I was adding too many people into the group, so much so, that at one point I was left to wonder whether the group ‘Hangout!’ is losing its essence.

A caricature of Hangout! group, as drawn by one of my close friends, Christine

Despite my personal disappointment at one point, I still stay in the group. Indeed, the fact that I will soon pursue a two-year research postgraduate program in HKUST gives me another chance to organize more hangouts with people within that group. I am still hoping that this chat group can once again become a ‘safe haven’, in particular, for people who are craving for friendships, so that they can join future hangouts that I want to organize for, at least, the next two years.

After some thought, I would even say that with the presence of this group, I have had some of the most cherishing years in my university life. It is the same people within the group that I can freely share my ideas, insight, imagination, thoughts, and in turn, to know and understand even better people of various backgrounds. It is not necessarily the hangouts themselves per se that always gave me encouragement; it is my friends within that group, and even those who have left, that my life becomes more slightly more colorful. All this would not have been imaginable had I chosen to continue staying within the comfortable confines of my own hometown.

To recap, here are some of the moments that made myself proud of having ever studied in HKUST:

- Initiating Humans of HKUST project: originally just thinking of it as a ‘one-off’ project in order to graduate from Redbird Award Program, the project ends up spanning for more than 3 years already, now entering its fourth year with the recruitment of a new project management team. Since the release of the first photograph book in 2015 together, each of the successive teams has also managed to get another book published every year (in both 2016 and 2017), each of which contains interviews and portraits of various individuals working and studying in the university

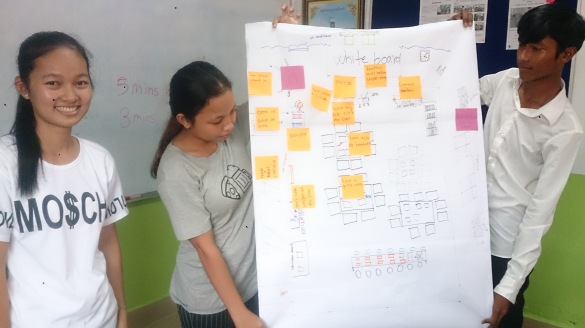

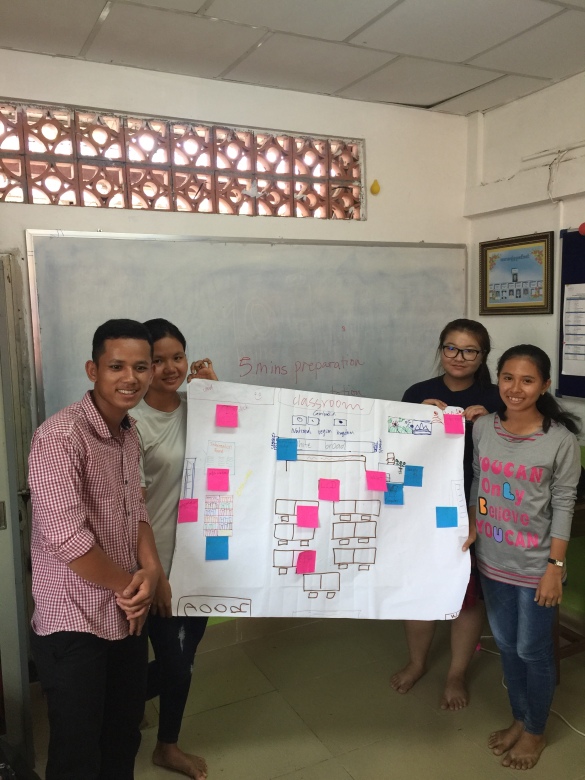

- Participating in SIGHT program: the program truly opened my eye about the essence of multidiscplinary cooperation. It also challenges me to go beyond the context of my academic study: without any proper programming background, I was tasked to perform user-experience (UX) research and user-interface (UI) designs for mobile health program for our healthcare NGO partner in Cambodia, One-2-One. I ended up designing over 60 different UI designs for the mHealth program for the coding team, all of which I used only pencils and A4 paper sheets. That was also where I began to learn and apply the concepts of design thinking

- Hangout!: I created the group in February 2015, originally just to organize a Chinese New Year dinner. Since then, we have organized more than 20 different hangouts. It’s never a perfect group (we now more frequently share dank memes and talk random stuff), but I would say I’m glad the group continues to exist

- Getting Dean’s Lists for 5 times in the university, by which, thankfully, I could get scholarships to partially cover the tuition fees, as well as to reduce my parents’ financial burden

- Earning some salaries, for the first time, from working in various research projects, as well as doing other on-campus internships

- Having the opportunities to befriend people of numerous backgrounds

- Developing appreciation of artworks, and experimenting myself by listening to different genres of indie music (beyond the pop-culture mainstream music)

Beyond the moments that made me proud, I have also undergone through multiple ‘failures’ throughout the same period:

- I have yet to fully exercise my emotional restraints when under intense pressure, especially in group projects, or whenever I was jokingly teased out by some of my friends

- I have had crush on 4 female friends, but none of them materialized into a relationship. For now, I’m putting my relationship efforts on hold

- Getting rejected by all the universities in the US I have applied for PhD in Political Science. I applied into 9 schools, and all of them ended up rejecting my PhD applications. At one point, I was rejected by Cornell, Stanford, and MIT on the same day. But I was not disastrously disappointed either: I was aware that my admission chances were really slim, but at least I have done my best. Moreover, I would rather see the failures as some kind of ‘divine intervention’, because deep down my heart, even if I succeed to receive and accept a PhD offer, I absolutely have no idea about my mental readiness about the future challenges that I may have encountered in relation to that PhD program. As an alternative, I actually received Master’s offers from NYU and U.Chicago. NYU did not offer me any single scholarship, and University of Chicago offered me a 50% scholarship, but even with the 50% ‘discount’, my parents would still be unable to support my studies. I ended up rejecting their offers, and accept my offer for a research postgraduate program in HKUST instead

- Having my papers rejected for publication or even consideration into academic journals, despite extensive literature reviews

- I was rejected for multiple scholarship programs that I had applied. What hurt me even more was the typical, unsympathetic reply from the university staff, who simply wrote that “I should try even harder”, when I have spent like 50-80 hours per week doing university-related assignments and projects

- I have yet to learn to be fully forgiving of others and forgiving of myself of past mistakes

- I failed to maintain a work-life balance. Instead, for now I have ended up adhering to “work-life integration”

And then the things that I did not regret:

- My major: occasionally I used to question the efficacy of my Global China Studies major, but through gradually accepting my uniqueness, and all the valuable learning that I have attained in this program, I would say that I did not regret enrolling in this major. Indeed, it enriches my research interests, and it increases my knowledge significantly. Moreover, a human being is more than what others would impose an academic label on: I do not want to be associated solely with my major alone

- Trying new things and fail: one example was enrolling in Entrepreneurship minor offered by the university. I took some minor courses, but instead, the course grades ended up depleting my CGA consecutively for two semesters. I had to maintain my CGA in order to continue my eligibility for annual scholarships, and in order to ‘salvage’ the grades, I decided to quit the minor program. However, I have never had a single regret doing the minor program, and neither have I regretted quitting it

- Studying in HKUST: despite my initial culture shocks and struggles to assimilate myself with this university, I eventually ended up enjoying my university life here. Despite the constant pressure and challenges related to courses, projects, exams, research projects, and papers, this is also the place where I began to understand what a “true friendship” means to me

- Not doing an exchange program: the reason why I did not do an exchange program was primarily because of the ongoing ‘culture shock’ that I still partially experience in the university, even after almost 4 years. Instead, I made use of all 8 semesters by getting myself as much engaged in research projects and other activities as possible

And then the things I regret, and I wish I had changed my mindset earlier:

- I wish I had exercised patience earlier in almost any aspect

- I wish I had captured more opportunities to do travel. Indeed, I had foregone too many opportunities throughout my undergraduate life to travel, mostly for various ‘reasons’, like doing papers, unexpected expenses, and numerous other factors

- I wish I had attained a better work-life balance. Although I have had Hangout! group, I actually do not organize many hangouts. Many places, even in Hong Kong, are left unexplored. Indeed, I mostly divide my time between classes, meetings, library, and my own dorm room. Reflecting back at what I have done, I actually regretted not spending more time with friends and visiting other places across Hong Kong, or even doing travels abroad

- I wish I could learn to fully trust people. I occasionally have moments of paranoia, and sometimes, I can be easily suspicious of others, even on the strangers. Now I regret that I have placed too much mistrust on people; I wish I exercised better self-control over my own mind

Lastly, my own advice for friends who have yet to graduate, or who will soon be in universities, especially into HKUST:

- Seek opportunities elsewhere: and it’s entirely up to you whether you want to pursue as many opportunities as you can (if you can manage with adequate time), or you would rather be more selective

- Explore new places: even if you are not really fond of overseas traveling, at least places within our vicinity (say, within the city, or any other geographic locale, where the university is located) can be a good start. Regardless of all the pressure imposed by courses and projects, do not allow them to wreck our work-life balance

- Keep oneself open-minded: having been raised and undergone through pretty much the same cultures and values for the 18 years of my life, I found it a big struggle when it comes to adapting to such an outside-a-comfort-zone studying experience. The only key thing I can suggest is to keep ourselves open-minded, and appreciate others’ cultures and customs

- Appreciate our parents’ sacrifice: in most circumstances, it is our parents who have funded our university education, and I can not thank my parents enough for the huge sacrifices they have made in order to support my studies in HKUST, so much so that they need to exercise fiscal austerity to save enough money. That ‘pressure’, to some extent, also pushed me to work very hard in order to attain enough scholarships to partially cover my tuition fees

- Be honest with oneself: we do not have to be someone else to make other people like us. Just be as authentic as we always are, but if there are bad habits and/or bad traits, do make efforts to address these issues

- It’s okay to sometimes cry: living overseas has never been easy. Sometimes pressure is so huge that we occasionally do not know to whom we can share our grievances. I would say, it’s normal to express our emotions, even if we need to shed our tears occasionally

Wrapping up this blog post, I want to convey my deepest appreciation for anyone who has become my friends, my close friends, my best friends, and those who have given me constant encouragement and powered me with enough resilience throughout my studies in this university. I also want to deeply thank my aunt, my cousin, my uncle, and in particular, my parents and my younger brother, all of whom have given me a tremendous mental support and a source of comfort.

Let me close this post with a quote by Paul Bowles for one of his works (The Sheltering Sky), which became an inspiration for Japanese musician Ryuichi Sakamoto to craft a musical piece – title: fullmoon, in his album Async (2017) – in honor of the American author.

“Because we don’t know when we will die,

We get to think of life as an inexhaustible well.

Yet everything happens only for a certain number of times,

A very small one, really.

How many more times will you remember,

A certain afternoon in your childhood?

Some afternoon, that is so deeply a part of your being,

That you can’t even conceive a life without it

How many times, four or five times more,

Perhaps none even left,

How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps 20.

And yet it all seems so limitless.”