Although I am not from Jakarta, I was personally disappointed – but not too surprised – at the outcome of the second-round gubernatorial election in the capital of Indonesia, which was held this Wednesday, on April 19.

For a backgrounder, let me explain briefly about the electoral race.

On one side, there is the incumbent governor, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, the city’s first ethnic Chinese – and second Christian – leader. Known by his Chinese nickname “Ahok” (as it is Hakka pronunciation for the last character of his Chinese name, 锺万学), he has taken over the position as the governor of this city of 10 million since November 2014 after his predecessor, Joko Widodo, also known as his political ally, undertook the position as the 7th President of Indonesia. On the other hand, there is his rival, Anies Baswedan, a Yemeni-descended US-educated technocrat and former Minister of Education who has been – very recently – pandering to the more hard-line Muslim organizations, all under full support by opposition parties led by the former 2014 presidential candidate, retired general Prabowo Subianto, who was also Widodo’s rival. Pairing with Baswedan is Sandiaga Uno, a US-educated businessman and billionaire investor, who has gained notoriety after his name was included in Panama Paper leaks. Pairing with Ahok, meanwhile, is Djarot Saiful Hidayat, the current deputy governor.

What made the 2017 gubernatorial election so unusual compared to other local elections in Indonesia was the massive scope – and also considerable controversy and polarization – related to the two candidates. The hype started in the aftermath of Ahok’s alleged blasphemy against Islam in June 2016, when he encouraged people of Jakarta not to be easily deceived by certain political forces using Verse 51 of Chapter 5 of the Quran (known as Surat Al-Maidah) to block him, the content by which contains restriction for Muslims to vote for non-Muslim leaders in Muslim countries. Somebody in YouTube intentionally revised his speech, subsequently editing it into “encouraging people not to be easily deceived by Verse 51 of Chapter 5 of the Quran”. Although the editor had been arrested himself and Ahok had repeatedly clarified his statement – and even issued multiple apologies, the snowball was just becoming too big to handle. It culminated in mass protests in November and December 2016 – many of which were led and supported by hard-line Muslim organizations, demanding Ahok’s dismissal as governor, his imprisonment, or even openly calling out to “kill Chinese”, referring to his ethnic Chinese origin. Simultaneously, he was immediately named a blasphemy suspect, and has since been attending weekly trials in one of Jakarta’s district courts. All this was happening at the same time he was running for gubernatorial race.

The controversy further took place when Baswedan – long known as a moderate-leaning Muslim, and even nominated by Foreign Policy magazine as one of the world’s most influential intellectuals back in 2008 – met several times with the same hard-line Muslim leaders who had been leading mass protests against Ahok, oftentimes even showing open support for their action. He was subsequently supported by a coalition of parties led by Prabowo Subianto – a former general and presidential candidate in 2014 also associated with his own controversies, allegedly human rights abuses in the Suharto era. In the second round of the election, Baswedan – whose only governmental experience was being Minister of Education under Widodo administration – won decisively against Ahok; based on the ongoing tallies by the election commission, 57% of eligible votes went to Baswedan – as opposed to 43% to Ahok.

And all this was happening when Ahok’s approval rating as the governor was over 68%. That means although some people openly approved of Ahok’s achievements throughout his tenure, a considerable percentage of them actually decided – ironically – to vote him out of office.

Briefly speaking, his achievements – first as deputy governor (2012-2014) and later as governor (from 2014 onward) – had been his efforts at budget reforms (computerizing the budgeting system under joint supervision with Indonesia’s anti-corruption agency), infrastructure construction, bureaucracy reforms, public housing for the low-income and poor, public transportation, flood-control measures (due to Jakarta’s recurrent flood seasons), as well as social welfare, particularly in education and healthcare. What was significant, in particular, was his flood-control measures, which involved cleaning up rivers, and most controversially, evicting a large number of riverside communities to pave way for canal normalization, the alternative by which was their relocation to government-built apartments. This, actually, became a source of consternation and alienation for some of the affected people, many of whom had previously shown support for both Widodo and Ahok in the preceding 2012 gubernatorial election.

Despite his achievements, he had been barely short of controversies – even before the alleged blasphemy. He was known for his “Sumatran” talking style (a stereotypical way to describe outspoken, loud-talking, and perceivedly-rude people, but I’m from Sumatra too), and not infrequently his past statements had offended a significant number of individuals – mostly politicians and bureaucrats whom he accused of “manipulating taxpayers’ money”. His shortcoming, in this regard, was his ill-temper. His controversies notwithstanding, he has remained largely popular among a substantial percentage of people in the city, given his informal and direct way of communication. He has several hotline numbers so that people can directly report to him for problems within the city, and has even personally attended wedding events of ordinary Jakarta people – as long as they extended invitation to the governor.

It is inevitable that the blasphemy charges against Ahok had cost him a considerable amount of political support. Indeed, the gubernatorial election has been extensively covered in international media, most of which has the theme of “an ethnic Chinese Christian governor pitted against an ethnic Arab Muslim candidate supported by hard-liners”. The New York Times called it “a referendum on pluralism versus Islamism”. Some observers even considered Anies’ electoral victory as “an omen to Indonesian democracy and respect for diversity”. And personally speaking, I was disappointed. But there are way more complicating explanations behind his victory. For some perspectives, I would rather use a half-glass-full than half-glass-empty approach.

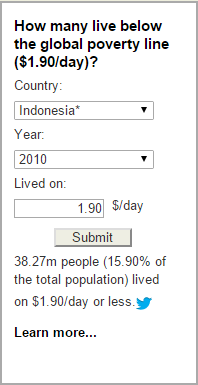

First, to have secured over 43% of voters’ support despite the ongoing blasphemy trials has itself been a progress for Ahok. I admit that ethnic, racial, and religious overtones among supporters of both candidates had been particularly heated – and even at times nasty – especially when you look at social media posts (should you understand Indonesian), but we need to look at a bigger picture here: over 85% out of 10 million people living in Jakarta are Muslims. In this regard, over 1.5 million people in Jakarta are non-Muslims. As there are more than 7 million eligible voters in the city, if we referred to the 77% voter turnout in the first round of the election (close to 5.4 million people who went out and voted) – and if this turnout was sustained in the second round – that meant more than 2.3 million people actually voted for Ahok, a figure close to 2.36 million who voted for him in the first round. Obviously, a large proportion of his supporters are Muslims themselves, and not all non-Muslims necessarily showed their support to the incumbent. Therefore, this argument should defeat the overwhelming theme among international news stories as already mentioned in the prior paragraph. Also, many among Anies-Sandi supporters are non-Muslims, particularly ethnic Chinese local business elites who would opt for “business climate stability”. One of the pair’s most ardent supporters is Hary Tanoesoedibjo, an ethnic Chinese tycoon who controls 4 out of 10 national TV stations, and oftentimes described as “Donald Trump of Indonesia” (because his most influential idol is Trump, and his presidential aspiration himself).

Second, to have an ethnic Chinese governor running Indonesia’s capital and most populous city less than two decades after deadly anti-Chinese riots is also another breakthrough. During the May 1998 riots that led to the ouster of Suharto’s 32-year authoritarian regime, most of the victims were middle- and lower-income ethnic Chinese whose shops and houses had been looted and burned, or who were themselves killed and brutally tortured. By November 2014, upon Widodo’s inauguration as President, Ahok – then his deputy – succeeded him. His appointment had been greeted by protests among hard-line organizations, but with his approval rating (by the end of 2016) remaining at 68% and with his governorship fairly smooth and stable (despite blasphemy charges), this has been itself a major achievement. All this happened within less than two decades, and to have this attained with minimum hurdles has never been an easy task.

Third, democracy in Indonesia is just barely as perfect as democracy in other countries. Sometimes, democracy is about choosing “a wolf in a sheep’s clothing”, with us oftentimes behaving ignorantly on who the heck that sheep is. And we have seen some of the worst examples of it: slightly above 50% of British voters opted for Brexit (only to search in Google on what on earth European Union is), many American voters went for Donald Trump despite having a relatively high (56%) approval rating of President Barack Obama (although Hillary Clinton secured nearly 3 million more votes than Trump, but thanks to electoral college). With the presidential election taking place in France as of the day I am writing this post, I would be very curious to see whether the far-right Le Pen, inexperienced-but-last-hope Macron, no-job-but-highly-paid Republican Fillon, or the communist, hologram-loving Melenchon would advance to the second round. Democracy, dangerously, can become a tool to elect somebody who may opt to end democracy once and for all. This is the age of political bubble and extreme polarization that we will continue to live in for the remainder of this century, as economic inequality, social media, and technological disruption continue to reshape our lives and how we view and manifest the world in ourselves.

Fourth, ethnic, racial, and religious sentiment is hardly new for this country. Democracy is only less than 20 years old in Indonesia, and like a typical teenager, it is not yet close to mature and emotionally volatile. Candidates in local elections have often touted their religious credentials – or proudly espoused their ethnic identities – as their “major recipe” to get elected to public offices, and not infrequently, this has been used as a tool to weaponize their rivals. People don’t get to change their mindset in a short term; depending on a country’s level of development, the change may either happen, or things will stay flat. This nation still has a long road to go to learn from its past mistakes.

Fifth, and lastly, Ahok still has the remaining 6 months as the governor, before his tenure is over on October this year. I am confident he is able to make achievements within this time period. For any successor – Baswedan notwithstanding – to dismantle his legacies will not be as easy as flipping over a paper.

These are the reasons why I refuse to believe that Ahok’s loss is a defeat for Indonesian democracy. Ironically, it is a dynamic principle of democracy itself: either you gain confidence among voters and they will vote for you, or that you do something wrong and they will vote you out. The irony is that frequent leadership turnovers hardly sustains long-term policy-making, but for better or worse, we are now living in an age of popular vote. Look at elsewhere across the world, and the distress is also there: many people are becoming disillusioned with democracy, political establishment, and all this stuff. Life, after all, has to go on. Moreover, most leaders – in the end – will no longer talk and act like they were as candidates; they would – adhering to the “median-voter theorem” – be hard-pressed to end up in the “center”. They would be pressed to accommodate the interests of all people, even the interests of constituents who had sided with their electoral rivals. The question is whether Anies and Sandi would be able to accommodate the interests of all people in the capital city.