Father’s Day is still two weeks to go, but you can present this great song to your beloved fathers (or simply commemorate them whenever they have already passed away). It’s one of the greatest pieces by Cat Stevens (now known as Yusuf Islam). Enjoy.

Father’s Day is still two weeks to go, but you can present this great song to your beloved fathers (or simply commemorate them whenever they have already passed away). It’s one of the greatest pieces by Cat Stevens (now known as Yusuf Islam). Enjoy.

Source: elonpendulum.com

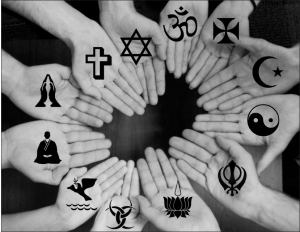

The essential meaning of every religion is to answer the question “Why do I live, and what is my attitude to the limitless world that surrounds me?” There is not a single religion, from the most sophisticated to the most primitive, which does not have as its basis the definition of this attitude of a person to the world.

At the heart of all religions lies a single unifying truth. Let Persians bear their taovids, Jews wear their caps, Christians bear their cross, Muslims bear their sickle moon, but we have to remember these are all only outer signs. The general essence of all religions is love to your neighbor, and that this is requested by Manuf, Zoroaster, Buddha, Moses, Socrates, Jesus, Saint Paul, and Muhammad alike.

Ewald Flugel (1863-1914), a German pioneer of study of Old and Middle English Literature and Language

Dear all religious extremists, please reconsider this quote.

Profile of Eduard Khil (anglicized as ‘Edward Hill’), a Soviet baritone singer who, in a string of fate, unexpectedly became an Internet meme phenomenon.

Get to know more about his biography in Wikipedia.

Excerpt:

Khil was born on 4 September 1934 in Smolensk to Anatoly Vasilievich Khil, a mechanic, and Helena Pavlovna Kalugina, an accountant. Life as a child was hard on Khil. With his family breaking up, he was brought up by his mother. During the Great Patriotic War (WWII Eastern Front), his kindergarten was bombed, he was separated from his mother and evacuated toBekovo, Penza Oblast where he ended up in a children’s home, which lacked basic facilities and needs, such as food. Despite this Khil regularly performed in front of wounded soldiers in the nearby hospital.He was reunited with his mother in 1943 when Smolensk was liberated from Nazi Germany and in 1949 moved to Leningrad, where he enrolled and then graduated from printing college. In 1955, Khil enrolled in the Leningrad Conservatory, where he studied under direction of Evgeni Olkhovksky and Zoya Lodyi. He graduated in 1960.During his studies, he began performing various lead operatic roles, including Figaro in The Marriage of Figaro.

Bonus: read more about the ‘lololol’ phenomenon in Internet Meme Database.

Last bonus: watch the Eduard Khil’s original ‘trololo’ video, which was published in early 1970s in Soviet television.

An ordinary, 9-to-5 Japanese middle-class man meets a human-sized frog, offering him a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to fight a monstrous underground monster that will, soon or later, demolish Tokyo.

Read this Murakami’s surrealist short story, published in June 2002, in GQ.

Excerpt:

“I know I should have made an appointment to visit you, Mr. Katagiri. I am fully aware of the proprieties. Anyone would be shocked to find a big frog waiting for him at home. But an urgent matter brings me here. Please forgive me.”

“Urgent matter?” Katagiri managed to produce words at last.

“Yes, indeed,” Frog said. “Why else would I take the liberty of barging into a person’s home? Such discourtesy is not my customary style.”

“Does this ‘matter’ have something to do with me?”

“Yes and no.” Frog said with a tilt of the head. ” No and yes.”

I’ve got to get a grip on myself, thought Katagiri. “Do you mind if I smoke?”

“Not at all, not at all,” Frog said with a smile. “It’s your home. You don’t have to ask my permission. Smoke and drink as much as you like. I myself am not a smoker, but I can hardly impose my distaste for tobacco on others in their own homes.”

Katagiri pulled a pack of cigarettes from his coat pocket and struck a march. He saw his hand trembling as he lit up. Seated opposite him, Frog seemed to he studying his every movement.

“You don’t happen to be connected with some kind of gang by any chance?” Katagiri found the courage to ask.

“Ha ha ha ha ha ha! What a wonderful sense of humor you have, Mr. Katagiri!” Frog said, slapping his webbed hand against his thigh. “There may be a shortage of skilled labor, but what gang is going to hire a frog to do their dirty work? They’d be made a laughingstock.”

“Well, if you’re here to negotiate a repayment, you’re wasting your time. I have no authority to make such decisions. Only my superiors can do that, I just follow orders. I can’t do a thing for you.”

“Please, Mr. Katagiri,” Frog said, raising one webbed finger. “I have not come here on such petty business. I am fully aware that you are Assistant Chief of the lending division of the Shinjuku branch of the Tokyo Security Trust Bank. But my visit has nothing to do with the repayment of loans. I have come here to save Tokyo from destruction.”

An in-depth, 228-page investigation of the decades-old political crisis which has, over and over, plagued Thailand, and how the monarchy, rather than offering the solutions, is instead aggravating the situation, the most recent of which is the reintroduction of military rule throughout the whole nation, and why this, if no compromise is formulated, will blow the country apart.

Download the full report from Zen Journalist, a blog run by Andrew MacGregor Marshall, former senior editor at Reuters.

Excerpt:

Of all the world’s countries, Thailand is among those for which the publication of the U.S. embassy cables could have potentially the most profound impact. All nations have their secrets and lies. There is always a gulf between the narrative constructed by those in power, and the real story. But the dissonance between Thailand’s official ideology and the reality is particularly stark and troubling. Suthep Thaugsuban, a senior (and notoriously corrupt) Thai politician, blithely claimed in December 2010 that the cables would have no impact on the country:

We don’t have any secrets… What happens in Thailand, we tell the media and the people.

His comments could scarcely be further from the truth. Thailand is a nation of secrets, and most of the biggest secrets are those involving the Thai monarchy. The palace is at the centre of an idealized narrative of the Thai nation and of what it means to be Thai, which depicts the country as a uniquely blessed kingdom in which nobody questions the established order.

Thais are well aware that the truth is very different — they could hardly be otherwise, following the violent political crisis that has engulfed their country — and yet many continue to suspend their disbelief and, at least publicly, to profess their faith in the official myths. Most feel unable to voice the truth, due partly to immense social pressure in a society where to question the official story is to be regarded as “un-Thai”, and partly to some of the strictest defamation laws in the world. At the heart of the legal structure protecting the official myth is the lèse majesté law. Article 112 of the Thai Criminal Code states: “Whoever defames, insults or threatens the King, Queen, the Heir-apparent or the Regent, shall be punished with imprisonment of three to fifteen years.” A law originally intended to shield the monarchy from insults and slander has become something far more: it is increasingly used to prevent any questioning of Thailand’s established social and political order. As historian David Streckfuss says in the foremost academic work on the subject, Truth on Trial in Thailand: Defamation, Treason, and Lèse Majesté: “Never has such an archaic law held such sway over a ‘modern’ society (except perhaps ‘Muslim’ theocracies like Afghanistan under the Taliban)”:

Thailand’s use of the lèse majesté law has become unique in the world and its elaboration and justifications have become an art. The law’s defenders claim that Thailand’s love and reverence for its king is incomparable. Its critics say the law has become the foremost threat to freedom of expression. Barely hidden beneath the surface of growing debate around the law and its use are the most basic issues defining the relationship between those in power and the governed: equality before the law, rights and liberties, the source of sovereign power, and even the system of government of the polity — whether Thailand is to be primarily a constitutional monarchy, a democratic system of governance with the king as head of state, or a democracy.

This TED-Ed video is extremely brief (just a little more than one minute), but it offers us a very powerful lesson: be careful, and be wise, for all the words we use, as illustrated by this concluding story of an Auschwitz survivor Benjamin Zander, a musical composer, gave during his 2008 TED talk.

Watch it, and let us try to realize how words, for all their seeming simplicity, carry such a power we can’t ever take for granted.

Optimism, or Pollyanna you want to call it, has remained an inseparable trait of human nature. We need optimism as it gives us silver linings for all possible positive consequences of everything we see, whatever we do, or how the reality perceives us to be. The belief that the world will be a better place than yesterday, that our future will be more fulfilling than the lives we are living today, or that we will find our eternal love life, thus giving no spaces for all unexpected occurrences.

Up to that point, however, optimism has shown itself to be a bias. When we are being tottered with our ‘rose-tinted spectacles’ about reality, that things will go smooth as everything is under control, that our marriages will go well with zero probabilities of divorce, or that our career will flourish with little or no stains, we often overlook any harbingers, any dangerous signs that may have been lurking deep within it, all beyond our vision.

Things strike like we never predict, afterwards. 40% of marriages in Western world (where most people surveyed dismiss any possibilities of a split) end up in divorce, millions of people are laid off, accidents happen, financial collapse is inevitable, etc, etc. Optimism bias, one that has so blinded us with way too many positive interpretations about the reality, instead becomes our own double-edged sword.

Cognitive neuroscientist Tali Sharot will talk in details about optimism bias from numerous aspects and ways we can do to handle its side-effects.

Listen, and think again.

Today, 16 years ago, one of Asia’s longest-running Western-backed dictators announced his resignation, ending a three-decade authoritarian rule in Indonesia, the world’s fourth most populous nation. It started with a savage pogrom; Suharto, assisted by CIA, launched an anti-Communist mass extermination campaign, killing 1-3 million civilians from 1965 to 1966. It ended, also, with another bloody wave of revolution; massive student protests, a brutal military crackdown, and afterwards, riots against ethnic Chinese, killing in between 1,000 and 5,000 people.

Then Indonesia undergoes through Reformasi, a political experimentation set on democratizing the country, and also eliminating all the elements of cronyism and corruption, the two things that used to sustain his rule as well as Indonesia’s fast-paced economic growth for three decades. Three direct elections have been scheduled, four presidents have followed through, and the nation, once economically devastated by the impact of 1997 Asian financial crisis (which obviously exposed how fragile the nation’s financial strength was, in particular due to corruption and shadow banking), again rebounds. GDP has surpassed 1 trillion US$, 100 million Indonesians have entered either middle or lower-middle class, and optimism has once again spread.

But, in this post-Suharto era, as well, Indonesia has lost one important element the dictator once used to preserve so well: stability. Islamic fundamentalism is on its rise. Corruption, rather than centralized in Jakarta, has instead been absorbed in hundreds of new regencies and cities formed in the wake of mass autonomy, and as a consequence, local dynasties, or the ‘mini-Suhartos’, have mushroomed across the nation. The Economist even warns us that our global crony-capitalism rank has increased significantly, from 18 in 2013, to 10 this year. Political configuration turns out to be even more helter-skelter than it once was in New Order. And all these, in current times, are inevitable.

Pankaj Mishra, an Indian novelist, tries to examine in details the post-Suharto Indonesian society in his essay in London Review of Books. Read it, and rethink.

Excerpt:

Under Suharto, Indonesia’s economy grew on average 6.5 per cent per annum for thirty years before contracting by 13.6 per cent in 1998. A culture of bribes and extortion flourished, but it wasn’t incompatible with high growth. Development subsidies from the West and Japan ensured a rise in living standards even before Indonesia turned into an export-oriented country. An oil boom starting in the 1970s helped; rural incomes were boosted by the introduction of high-yield rice varieties; literacy rates, which had been abysmal, rose. Monopolies in cement, oil, timber, telecommunications, media and food were enjoyed by an indigenous business class that included Chinese-Indonesians as well as members of Suharto’s family (he didn’t trust other Indonesian business families). Local companies were allowed to make deals with multinationals; ExxonMobil moved into Aceh to operate its gas fields; Freeport and Rio Tinto acquired mining rights in Papua. Military rule opened the floodgates for the corporate class, and small windows to the middle class. Many salary-earners and members of the urban petite bourgeoisie supported Suharto (they’re the ones mourning the demise of his ‘stable’ regime), whose Golkar party ensured that some of the loot trickled down to low-level officials. Even conservative Islam was eventually brought into his patronage networks.

Suharto’s careful sharing of the spoils eradicated any lingering elements of Sukarno’s national project, supposedly dedicated to the welfare of the people (rakyat). In 1988, the playwright and publisher Goenawan Mohamad braved censors to write nostalgically of Sukarno, who had died in disgrace in 1970: ‘When Bung Karno was alive, Indonesia still had the ideals of a Kshatriya’ – a member of the spartan elite in Hinduism’s old social order – ‘who owns no credit card, no BMW and no Black Drakkar aftershave. In Bung Karno’s time, Indonesia was still felt as an aim, a reason to fight, a cause. Now we don’t seem to be like that – and we feel that we have lost something.’ Indonesia, Mohamad wrote, was now merely a name for a territory populated by ‘stomachs, ambition and anxiety’.That was what Suharto wanted: a population divided by individual pursuit of food, wealth and status was the basis of his regime’s stability. It was also what finally tripped him up. Having entered the age of financial capitalism early, debt-laden Indonesia was also among the first to be exposed to its hazards. The currency lost nearly 80 per cent of its value in the wake of the crisis of 1997; per capita income collapsed; banks imploded; millions lost their jobs. The foreign investors who had been underwriting Suharto’s economic ‘miracle’ made themselves scarce. The IMF stepped in with its usual ‘rescue package’ of subsidy cuts, which led to food riots. A widely circulated photograph of the IMF director Michel Camdessus, arms crossed, looming over a seated and clearly supplicant Suharto recalled the humiliations of the colonial era.

A happy-sad story about foreign workers in Dubai, who fill up 90% of this city’s 2.1-million-strong population, and obviously, most of the jobs the Emiratis completely never want to: serving up the coffee on Starbucks, taking care of these Western expatriates’ kids, building bizarre-shaped skyscrapers, assisting customers at splurge shopping malls, and a long list to go.

Read the full article on National Geographic Magazine.

Bonus: click this Wikipedia article to find out, in details, a table of countries’ list with the world’s largest foreign-born population.

Excerpt:

No other city on Earth, though, packs 21st-century international workers into one showy space quite like Dubai. Arrive in the standard manner, disembarking into the sprawling international airport, and you will pass a hundred remittance workers like Teresa and Luis before you reach the curbside cabstand. The young woman pouring Starbucks espressos is from the Philippines, or maybe Nigeria. The restroom cleaner is from Nepal, or maybe Sudan. The cabdriver, gunning it up the freeway toward downtown Dubai, is from northern Pakistan or Sri Lanka or the southern Indian state of Kerala.

And the mad-looking, postmodernist skyscrapers outside the taxi windows? This building, the one like a massive hatchet blade, or the one that resembles a giant golf ball atop a 20-story pancake stack? All built by foreign laborers—South Asian men primarily, from India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. If it’s daylight, empty buses will be parked in the shade beneath the skeletons of the skyscrapers still under construction. They’re waiting to carry men back at dusk to group-housing units, crowded as prison barracks, where most of them are required to live.

Difficult living conditions for foreign workers can be found everywhere in the world. But everything about Dubai is exaggerated. The city’s modern history starts just over a half century ago, with the discovery of oil in nearby Abu Dhabi, then a separate and independent sheikhdom. The United Arab Emirates was founded in 1971 as a national federation encompassing six of these sheikhdoms—the seventh joined the following year—and since Dubai had comparatively little oil, the city’s royal family used its portion of the country’s new riches to transform the small trading city into a commercial capital to dazzle the world. The famous indoor ski slope is only one wing of a Dubai shopping mall, which is not even the biggest of the city’s many malls; that one contains a three-story aquarium and a full-size ice hockey rink. The tallest building on the planet is in Dubai; Tom Cruise was seen rappelling down its outer wall in one of the Mission: Impossible movies. Nearly everywhere the visitor looks, things are extravagant and new.

Miya Tokumitsu challenges us to rethink what that ‘do-what-you-love’ jargon – the one unceasingly promoted by dreamers, and other so-called ‘the one percent’ like Steve Jobs and his counterparts either in Wall Street or any paramount, top-of-the-world position – actually means.

The main point is, in brief, and also a hint before you start reading her essay, she is not asking us, the 99 per cent, the so-dubbed ‘corporation-exploited world proletariat’, to rebel against those ‘DWYL’ elites (although she implicitly makes a slight correlation with that notion, but okay, no ideologies are perfect though).

Read her thought-provoking, left-leaning essay in Jacobin (an American magazine with similarly left-wing theme), and contemplate it deeper.

Excerpt:

One consequence of this isolation is the division that DWYL creates among workers, largely along class lines. Work becomes divided into two opposing classes: that which is lovable (creative, intellectual, socially prestigious) and that which is not (repetitive, unintellectual, undistinguished). Those in the lovable work camp are vastly more privileged in terms of wealth, social status, education, society’s racial biases, and political clout, while comprising a small minority of the workforce.

For those forced into unlovable work, it’s a different story. Under the DWYL credo, labor that is done out of motives or needs other than love (which is, in fact, most labor) is not only demeaned but erased. As in Jobs’ Stanford speech, unlovable but socially necessary work is banished from the spectrum of consciousness altogether.

Think of the great variety of work that allowed Jobs to spend even one day as CEO: his food harvested from fields, then transported across great distances. His company’s goods assembled, packaged, shipped. Apple advertisements scripted, cast, filmed. Lawsuits processed. Office wastebaskets emptied and ink cartridges filled. Job creation goes both ways. Yet with the vast majority of workers effectively invisible to elites busy in their lovable occupations, how can it be surprising that the heavy strains faced by today’s workers (abysmal wages, massive child care costs, et cetera) barely register as political issues even among the liberal faction of the ruling class?

What do YOU think?

Random Outbursts of Energy: A Portfolio

An independent thinker's blog on everything

bits and pieces

Stop. THINK. Do.

For lovers of reading, crime writing, crime fiction

Indonesia business spotlight

A Creative Monkey On How To Find Your Path In Life.

Who is my ideal reader? Well, ideal means non-existent. I have no notion of whom I’m writing for. Guy Davenport

مواظب باش رنگی نشی

An average movie blog for the average movie watcher

Internal Guidance

Scepticism * Humanism * Escapism

Short Biographies

Host of CNN’s flagship foreign affairs show, Washington Post columnist, New York Times bestselling author

Creating content that captivates and connects

Articles, updates & views - from another angle than in your mainstream Western media

A bucket list blog: exploring happiness, growth, and the world.

It's simple, yet powerful.

this is still under construction, the main purpose of this blog is to correct and share valid information about africa, its people and culture

draws comics

Straight from my heart

the Story within the Story

a multi-hyphenate | journalist | actress | mc | moderator | public speaker

The CoF

Reflection

rights, politics, and goings-on in Asia

Inspiring, Encouraging, Healthy / Why waste the best stories of the World, pour a cup of your favorite beverage and let your worries drift away…

Nothing is impossible

International Economic Affairs & Relations / Regional & International Organizations / Global Commerce & Business

Fun Learning Resouces for Kids

an education reform blog

Give Yourself Away

A Place of Bewildering Complexity.

concerned with the issues and ideas of the contemporary city.

Thought Leadership

** OFFICIAL Site of Artist Ray Ferrer **

Don't ever change yourself to impress someone, cause they should be impressed that you don't change to please others -- When you are going through something hard and wonder where God is, always remember that the teacher is always quiet during a test --- Unknown

dahlaniskan.wordpress.com

The wacky stories of a crazy lady.

Journalist/Social Justice Campaigner/Education & Business Consultant

Short reviews on high quality films. No spoilers.

Blog with Journalistic and Historical articles

alaska, travel, photography, skiing, and what not

Maximize your creative life.