I was inspired – or honestly speaking, ‘triggered’ – to write this blog post in response to an op-ed post by Justin Fox in Bloomberg View about, as the title says, ‘who will get spillovers when US universities begin to lose out’. The author provided a brief overview of how Swiss universities can – at least temporarily – ‘pick up the cherries’ when Donald Trump administration’s future policies will pose challenges to the ongoing dominance of US universities. However, as constrained in terms of wording and space as the op-ed post is, the author only provided a brief comparison of both American and Swiss universities, citing presidents of the latter’s two universities (ETH Zurich and University of Zurich), who were both US-educated and had experiences working in the States.

What particularly motivated me to write this blog post was the university ranking index used by Fox in his op-ed article. Using the Shanghai-based Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU), which heavily emphasizes on measuring university-based research output and quality, I observed in details about changes in the ranking of universities across the world. As Fox had previously argued, as of 2016, US universities remain ‘the envy of the world’, with 15 out of the world’s best 20 and 50 out of the world’s best 100 universities based in the country. However, in spite of the ongoing dominance, this figure has showed a gradual decline from previously 17 and 54 back in 2007, or nearly a decade prior. Most of the universities that remain within the best hundred are private, bestowed with huge amounts of endowment, either from big corporations or rich alumni networks. Majority of the country’s public universities, on the other hand, continue to ‘stagnate’ due to cutbacks in expenditure and lack of research funding support.

On the other hand, universities across the Asia-Pacific region have shown a strong increase in rankings within the last decade, the largest driver by which is from China. With the exception of Japan, many countries here – in general – have seen a tremendous improvement with regard to the university rankings, mostly due to huge investments in the universities, but to some extent, also due to the declining position of several universities in the Western region, namely in North America and Europe. Here, I did a bit of research to compare and contrast the representation of regions in terms of their top educational institutions between 2007 and 2016, using the ARWU index.

The increasing mobility of capital, talents, and ideas has been particularly beneficial to Asia-Pacific region, as many top universities here seek to globalize their education outlook by hiring either US-educated or European-educated faculty members into their universities, as well as increasing collaboration with other counterparts across the region and the globe. Americas and Europe, on the other hand, have seen the numbers significantly decline, especially the former.

Let us look at the ‘top 20’ composition in the table below.

Within the last 10 years, US universities continue to dominate the top 20 ARWU list, although there was a slight decline due to increasing competition from institutions from other countries (as we can see from above, UK and Switzerland). However, the race to completely ‘drive out’ the existing education superpower remains a very long road to go – or, should I say, an implausible notion up to now; schools like Harvard, Stanford, Yale, and MIT continue to receive massive amounts of endowments, attract top-notch talents across the globe, and their global influence in many aspects (Nobel laureates, startup unicorns, research funding, huge alumni network support) remains unmatched with those in the rest of the world, and expect this to continue for decades to come.

The pattern remains pretty much unchanged when we expand the list into the ‘top 100’, as shown in another table below this sentence.

Within one decade, universities in Asia-Pacific (namely Australia, China, and Singapore) and in Western Europe (Belgium, Denmark, Netherlands, and Switzerland) began to take a small-yet-significant portion of the “top 100” ARWU list. Japan was an ‘exception’ when compared to most Asian countries, as its pattern largely echoed that of the United States; there was a significant decline in the number of top-notch universities, and when we looked further into the next two tables below – especially in the top 500, Japan’s decline is even more dramatic.

Caveat: you suspect Japan’s decline is because the ranking index is crafted from China (an arch-rival)? Not necessarily.

Expanding the list further to the top 200, I found out that the gap between countries experiencing increase and those facing decline is becoming increasingly larger.

With regard to the increase, China has experienced the biggest increase in the number of top-200 institutions, with a six-fold increase within a decade (2 in 2007 to 12 in 2016). Saudi Arabia, surprisingly, also has 2 universities within the top-200 list (from previously 0 in 2007); this may be largely thanks to the kingdom’s extremely large amount of endowments, and the existence of King Abdullah University of Science & Technology (KAUST, not to be confused with South Korea’s KAIST). South Korea has also seen its number tripling, from 1 in 2007 to 3 in 2016.

Unfortunately, the biggest “loser” in this list is once again the United States. Having 88 universities in the top-200 list in 2007, the number has since declined significantly to 71 last year. The impact of 2008-2009 financial crisis is particularly severe for public universities, and it remains reflected in the number of the institutions per se.

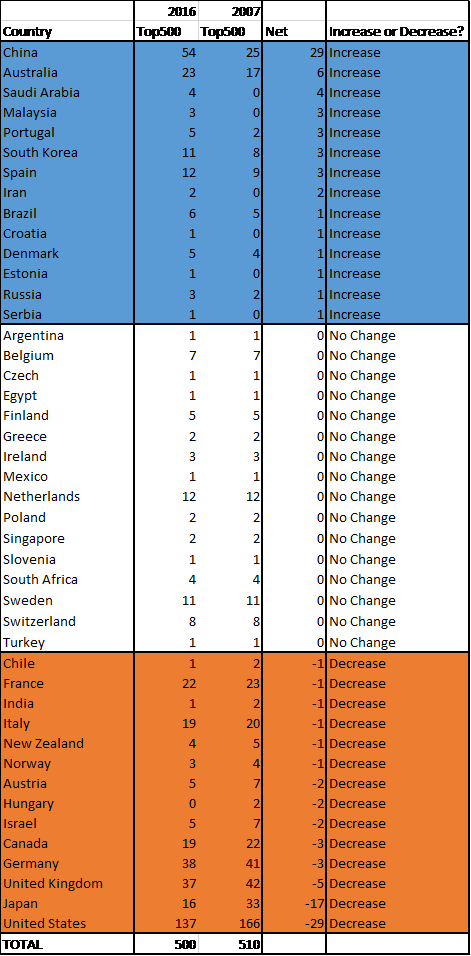

Lastly, let us take a final look at the ‘top-500’ list, as seen in the table attached below.

The biggest increase, once again, predominantly took place in Asia-Pacific countries, with countries that are particularly outstanding include China (a net increase of 29), Australia (a net increase of 6), Saudi Arabia (from 0 to 4), Malaysia (from 0 to 3), South Korea (8 to 11), and Iran (o to 2).

By contrast, the biggest ‘losers’ here were the United States and Japan; US has seen a net decrease of 29 universities (from 166 in 2007 to 137 in 2016), but an even more dramatic decline was in Japan, with a net loss of over half of its universities of 2007 level (from 33 that year to 16 last year, a net decrease of 17 schools, a total decline rate above 50% of its original level).

Here are several country-specific findings with regard to the ARWU ranking index:

- China: increase in the number of Chinese universities in the top 500 list can be attributed to active efforts by Chinese government to attract overseas Chinese talents to shift research and/or other academic works back to China. However, there are a few caveats with regard to this finding worth cautioning. First, many of the overseas talents that ‘return’ to China retain their jobs overseas; this leads to the second point, by which a large proportion of them only work in the country as ‘visiting professors’, ‘visiting researchers’, or scholars employed on a work-contract basis. Do also note that many of the Chinese students aspire to go abroad to study, the most popular destination by which remains the United States. Refer to a working paper by David Zweig and Huiyao Wang (2012) about efforts by Chinese government to recruit overseas Chinese talents, as well as findings by Institute of International Education (IIE) about the composition of international students in the US.

- United States: Cutbacks in public funding for public universities has largely declined within the last decade, regardless of whoever is in the presidency (be it Bush Jr., Obama, or even Trump). On the other hand, endowments to private universities, particularly top-notch ones, continue to increase (except on 2016 fiscal year, by which most universities show a significant decline). Still, several public universities continue to show strong performance within the same time period, such as UC Berkeley, UC Los Angeles (UCLA), UC San Diego (UCSD), University of Colorado – Boulder, UT Austin, Ohio State University (OSU), Pennsylvania State University (PSU), University of Minnesota, etc.

- Japan: the country, ironically, is in a rather “sorry state” in terms of its relative performance compared to other countries in Asia. Although Japanese universities continue to churn out innovations and remains dominant in terms of number of Nobel laureates, this shows no impact on the improvement of the universities within ARWU list. One reason, according to Times Higher Education and Japanese education consulting firm Benesse, is the high degree of insularity among Japanese universities: resistance to opening-up under globalization and the limited interaction between Japanese scholars and academic communities across the globe may help explain why the stagnation continues.

- South Korea: the country continues to ‘shine’ in terms of its research output and technological innovation, and is increasingly active in pioneering international collaboration between Korean and other universities across the globe, with a particular emphasis on Asia and the United States. However, as economic growth slows down, many university graduates have simultaneously struggled to find jobs in the country, particularly as the economy remains dominated by large-scale business holdings (chaebol), and entrepreneurial culture has yet to fully challenge the former’s influence.

- Saudi Arabia: on one hand, it is a good thing to have some universities within the top-500 list (4 institutions), but their contribution to structural reforms within the country remains notoriously inadequate. Unemployment rate among the youth remains staggeringly high (around 30%), opportunities for social and economic mobility remain largely closed for minority groups (especially female), and the country continues to primarily rely on foreign expertise for academic and research activities (one example? Simply look at faculty list for King Abdullah University of Science & Technology).

- Malaysia: the country showed up on the ‘top-500’ list, but it continues to struggle in reversing the brain drain, by which Malaysia has been among the worst affected countries. Low wages for prospective graduates, as well as ‘positive-discrimination’ approaches by the government that continues to favor majority ethnic Malays in university admissions, are two factors that continue to push Malaysian talents to pursue education overseas. This is made all the worse with the ongoing currency depreciation it has faced in the last 2 years. Many of my Malaysian friends also share such experiences with me regarding their motivations in studying abroad.

- Indonesia: none of the universities in my home country appeared in the list up to now. Although this is only in ARWU index, the fact that no institutions show up is such a disappointment.

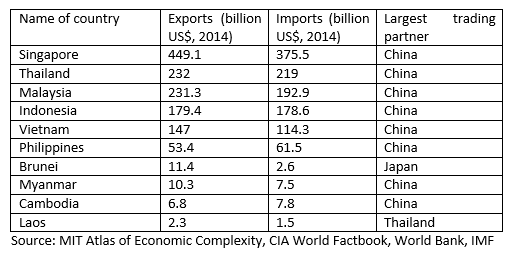

Conclusion: while the United States continues to remain dominant with regard to their education system, and is expected to remain preeminent for decades to come, its primacy is gradually being challenged with the rise of universities outside North America, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region. With globalization, the increasing mobility of talents, capital, and ideas across the globe will enable such educational spillover to continue taking place worldwide, especially with US-educated graduates either working in the States or taking up their career opportunities back in their home countries. It is also the same wave of globalization that will continue to motivate the best and the brightest across the world to come to US – and now an increasing number of alternatives in Western Europe and Asia – to pursue higher education. The monopoly remains largely concentrated in the Western world, but other regions (most importantly, Asia) are challenging up their domination.

Bonus: Times Higher Education releases what it calls 53 ‘international powerhouse’ universities, or those with very high research output and citation scores that can match the existing ‘superpowers’ like Ivy League schools or Oxbridge. It is not necessarily ‘global’, however, as 45 of these ‘powerhouses’ are still concentrated in the Western region (31 in North America, 14 in Europe), with the other 8 located in Asia-Pacific region. You can view the full list of these universities in the picture below.

Summary of the 53 universities based on countries they are located: